Headline News Archive

In March, the Florida Public Service Commission unanimously approved the Florida Power & Light Co. (FPL) SolarTogether program which will ensure the development of 1,490 MW of solar over the next two years making it the largest community solar program in the U.S. The program will help to propel the Sunshine State into a leadership position on solar development and reduce dependence on fossil fuels that contribute to climate change. This voluntary solar program puts participants in full control of their level of commitment. Customers can offset up to 100% of their electricity use with emissions-free solar. Read the article here.

In March, the Florida Public Service Commission unanimously approved the Florida Power & Light Co. (FPL) SolarTogether program which will ensure the development of 1,490 MW of solar over the next two years making it the largest community solar program in the U.S. The program will help to propel the Sunshine State into a leadership position on solar development and reduce dependence on fossil fuels that contribute to climate change. This voluntary solar program puts participants in full control of their level of commitment. Customers can offset up to 100% of their electricity use with emissions-free solar. Read the article here.

- Climate Communications Summit: https://mediasite.video.ufl.edu/Mediasite/Play/8aa5aa261eb349c39b0a01026161c1f51d

- Doug Parson's Podcast session is available here: https://mediasite.video.ufl.edu/Mediasite/Play/76ed71e2268840b9b810722d83b4c4af1d

The proposed Florida Climate Assessment will:

- Produce a strategic tool with standards, data, analyses, and thresholds for use in planning, decision-making, setting research agendas, and use in public policy and legislation

- Ensure resiliency decisions are informed by the best available science through an iterative, stakeholder driven process that is easily updated and user-focused

- Use the best science in a manner that is responsive, supportive, and critical focusing on systems and not separate sectors

- Improve relationships between knowledge producers and users and yield better decisions and outcomes to build capacity and overcome barriers

We want to know your thoughts on the proposed Florida Climate Assessment and its potential value to your work and to the state of Florida.

The Coastal Planning Program newsletter contains valuable science, policy, planning, risk and insurance, and economics resources for anyone working on coastal resiliency and planning in Florida and beyond. To check out the Sea Grant Coastal Planning page go to http://www.flseagrant.org/climate-change/coastalplanning/. Or, Please send an email to Thomas Ruppert requesting to be added to the newsletter mailing list.

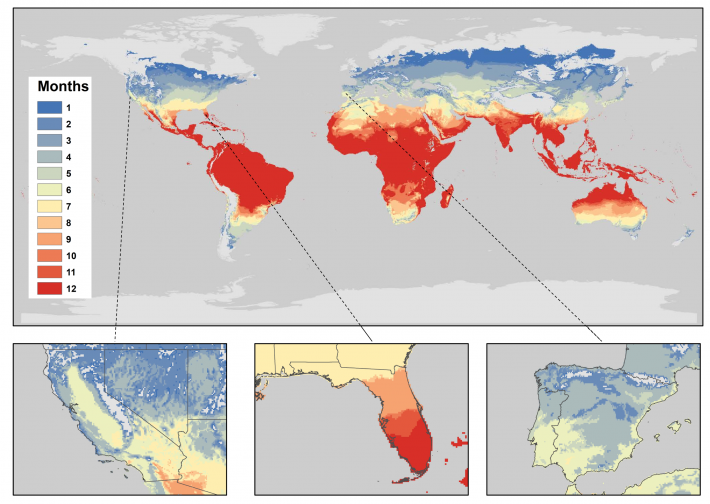

July 2, 2019 (By Kirsty Scandrett, University of Florida) - New research, published in Journal of Applied Ecology maps the peak temperatures for the establishment of citrus greening disease.

|

|

Orange juice is a staple on many breakfast tables, but the future availability of citrus products is threatened by the global spread of Huanglongbing (HLB), also known as citrus greening disease. The bacterium responsible for causing citrus greening prevents the formation of commercially viable fruit and is transmitted by an insect called the Asian citrus psyllid. Both the pathogen and the insect vector have been spreading in recent years, devastating regions famous for high citrus production and threatening the future of the citrus industry. As citrus greening becomes an increasing threat to growers worldwide, the future of the industry may depend on identifying locations that do not have a high risk of production collapse.

DELAND, FLA, JUNE 26, 2019 -- Stetson University has named Jason Evans, Ph.D., as the interim executive director of the Institute for Water and Environmental Resilience (IWER). His role begins on Aug. 15. Evans will fill the position while Stetson searches for a permanent replacement for Clay Henderson, J.D., who is retiring. Evans is an associate professor of environmental science and studies at Stetson as well as faculty director of IWER. Henderson’s Stetson accomplishments include developing and organizing IWER and its staff, including the advisory and faculty steering committees, affiliate faculty and endowment; creating and administering the Sustainable Farming Fund to incentivize sustainable agriculture in the Suwannee River basin; and planning and conducting fundraising associated with the Sandra Stetson Aquatic Center. Read the article.

DELAND, FLA, JUNE 26, 2019 -- Stetson University has named Jason Evans, Ph.D., as the interim executive director of the Institute for Water and Environmental Resilience (IWER). His role begins on Aug. 15. Evans will fill the position while Stetson searches for a permanent replacement for Clay Henderson, J.D., who is retiring. Evans is an associate professor of environmental science and studies at Stetson as well as faculty director of IWER. Henderson’s Stetson accomplishments include developing and organizing IWER and its staff, including the advisory and faculty steering committees, affiliate faculty and endowment; creating and administering the Sustainable Farming Fund to incentivize sustainable agriculture in the Suwannee River basin; and planning and conducting fundraising associated with the Sandra Stetson Aquatic Center. Read the article.

June 16, 2019 (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco) -- Climate change is already causing disruption to regional economic activity. Low-to-moderate income populations are highly vulnerable to these impacts, in part, because they often have fewer resources to adapt. The stability and prosperity of local economies in the face of climate change depends on how well the public, private, and civic sectors can come together to respond to the shocks and stresses of climate change. Collaborative efforts to fund climate adaptation not only reduce the burden on highly vulnerable populations, but they also offer the opportunity for co-benefits within a broader portfolio of community development ambitions.

This report introduces the field of climate adaptation finance and explains its connection to the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) within the context of the disaster provisions guiding pre- and post-disaster investments. In a demonstration of need, the report provides evidence of the spatial concentration of disaster declarations in areas with CRA-eligible populations. It highlights existing innovative and hypothetical investments within a broader context for stimulating greater pre-disaster planning and investment.

Community development practitioners, investors and policymakers will find this report useful for sparking new ideas about how to develop partnerships and funding streams for CRA-eligible activities—in both eligible communities and areas within a federal disaster declaration—that will reduce the vulnerability and increase the adaptive capacity of communities to the impacts of climate change.

Article Citation

Keenan, Jesse M, and Elizabeth Mattiuzzi. 2019. “Climate Adaptation Investment and the Community Reinvestment Act,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Community Development Research Brief 2019-5. Available at https://doi.org/10.24148/cdrb2019-05

June 2019 - The Florida Department of Environmental Protection has launched a new interactive algal bloom dashboard. This dashboard is a visual enhancement to the state's existing sampling slate. This data has been publicly available on DEP's website, but previously did not allow the public to easily see where algal blooms were occurring in Florida, in real time. The algal bloom dashboard features real-time updates of sample locations for up to 90 days and all available details related to those samples, such as photos and toxin information. Users can search by specific address, zip code, city or place. The tool includes quick links to other resources such as public health information.

June 2019 - The Florida Department of Environmental Protection has launched a new interactive algal bloom dashboard. This dashboard is a visual enhancement to the state's existing sampling slate. This data has been publicly available on DEP's website, but previously did not allow the public to easily see where algal blooms were occurring in Florida, in real time. The algal bloom dashboard features real-time updates of sample locations for up to 90 days and all available details related to those samples, such as photos and toxin information. Users can search by specific address, zip code, city or place. The tool includes quick links to other resources such as public health information.

June 2019 - Coral reef managers are faced with a crisis: deteriorating environmental conditions are reducing the health and functioning of coral reef ecosystems worldwide. These threats compound the persistent local stresses coral reefs have experienced for decades from pollution, overfishing, and habitat destruction. Established approaches for managing coral reefs are neither sufficient, nor designed, to preserve corals in a changing climate. A growing body of research on “coral interventions” aims to increase the ability of coral reefs to persist in rapidly degrading environmental conditions. Those interventions include activities that affect the genetics, reproduction, physiology, ecology, or local environment of corals or coral populations. A first report, released by the National Academy of Sciences in November 2018, reviewed the current state of the science for 23 novel interventions. This report provides a decision framework to help managers assess and implement interventions that are suitable for their region and goals. Get the report.

June 2019 - Coral reef managers are faced with a crisis: deteriorating environmental conditions are reducing the health and functioning of coral reef ecosystems worldwide. These threats compound the persistent local stresses coral reefs have experienced for decades from pollution, overfishing, and habitat destruction. Established approaches for managing coral reefs are neither sufficient, nor designed, to preserve corals in a changing climate. A growing body of research on “coral interventions” aims to increase the ability of coral reefs to persist in rapidly degrading environmental conditions. Those interventions include activities that affect the genetics, reproduction, physiology, ecology, or local environment of corals or coral populations. A first report, released by the National Academy of Sciences in November 2018, reviewed the current state of the science for 23 novel interventions. This report provides a decision framework to help managers assess and implement interventions that are suitable for their region and goals. Get the report.

May 2019 (Source: UF/IFAS News) Governor Ron DeSantis announced in April that University of Florida scientist Tom Frazer will be the state's first Chief Science Officer. Frazer will lead efforts to address some of Florida's most critical environmental challenges, including red tide and harmful algal blooms, which have impacted millions of Floridians, said Jack Payne, Working with the governor's staff, state agencies and a state-wide task force, Frazer will work to find science-based solutions to environmental issues important to Florida residents, according to a statement from the governor's office. "It's a great honor to be asked to serve in this role, and I'm ready to start working with state leaders and our best researchers to protect our water and our environment," Frazer said. This won't be the first time Frazer has headed a diverse team to tackle complex problems. As director of the UF/IFAS School of Natural Resources and Environment, Frazer led faculty members from 56 departments across 12 colleges, who worked on issues ranging from transitioning to renewable energy systems, preventing pollution, protecting biodiversity and climate change. Frazer will retain his faculty appointment at UF while serving as Chief Science Officer. Read the article.

May 2019 (Source: UF/IFAS News) Governor Ron DeSantis announced in April that University of Florida scientist Tom Frazer will be the state's first Chief Science Officer. Frazer will lead efforts to address some of Florida's most critical environmental challenges, including red tide and harmful algal blooms, which have impacted millions of Floridians, said Jack Payne, Working with the governor's staff, state agencies and a state-wide task force, Frazer will work to find science-based solutions to environmental issues important to Florida residents, according to a statement from the governor's office. "It's a great honor to be asked to serve in this role, and I'm ready to start working with state leaders and our best researchers to protect our water and our environment," Frazer said. This won't be the first time Frazer has headed a diverse team to tackle complex problems. As director of the UF/IFAS School of Natural Resources and Environment, Frazer led faculty members from 56 departments across 12 colleges, who worked on issues ranging from transitioning to renewable energy systems, preventing pollution, protecting biodiversity and climate change. Frazer will retain his faculty appointment at UF while serving as Chief Science Officer. Read the article.

May 2019 - Michael Volk, Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture, and Dr. Gail Hansen, Associate Professor in the Department of Environmental Horticulture at the University of Florida, have been awarded a California Landscape Architectural Student Scholarship (CLASS) Fund Research Award from the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA).

May 2019 - Michael Volk, Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture, and Dr. Gail Hansen, Associate Professor in the Department of Environmental Horticulture at the University of Florida, have been awarded a California Landscape Architectural Student Scholarship (CLASS) Fund Research Award from the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA).

This one-year project, entitled Future Landscape Professionals of the Anthropocene, will collect data on college curricula, teaching methods, and attitudes of students and teachers to identify and evaluate best practices for integrating climate change and climate-wise design strategies into landscape architecture and horticulture programs.The research team includes Dr. Belinda B. Nettles, Research Affiliate with the University of Florida's Center for Landscape Conservation Planning, and Isabella Guttuso, a Master of Landscape Architecture student. Project results will be posted on the Center for Landscape Conservation Planning's website Landscape Change. This website is part of the Center's broad initiative to advance climate-wise design and information sharing among landscape professionals.

April 2019 - A recently published book by Diana Mitsova and Ann-Margaret Esnard, Geospatial Applications for Climate Adaptation Planning, presents an overview of the range of strategies, tools, and techniques that must be used to assess myriad overlapping vulnerabilities and to formulate appropriate climate-relevant solutions at multiple scales and in varying contexts. Each chapter is grounded in the literature and presents case studies designed by the authors, as well as many examples from a diverse international group of scholars and entities in the public and private sectors. Areas covered include: Climate Change and Climate Adaptation Planning: Context and Concepts Geospatial Technologies: Fundamentals and Terminology GIS and Climate Vulnerability Assessments Technical Approaches to Formulating Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies Geospatial Applications for Climate Adaptation Planning is aimed at advanced students, researchers, and entities in the public and private sectors. It also provides supplementary reading for courses in planning, public administration, policy studies, and disaster management.

March 2019 - The latest national survey by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication finds that a large majority of Americans think global warming is happening, outnumbering those who don't by more than five to one. Americans are also growing more certain that global warming is happening and more aware that it is caused by human activities. Certainty has increased 14 percentage points since March 2015, with 51% of the public now "extremely" or "very sure" that global warming is happening. Sixty-two percent of the public now understands that global warming is caused mostly by human activities, an increase of 10 points over that same time period.This report analyzes American's increasing awareness and concern about global warming and its associated risks. Read the report.

March 2019 - The latest national survey by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication finds that a large majority of Americans think global warming is happening, outnumbering those who don't by more than five to one. Americans are also growing more certain that global warming is happening and more aware that it is caused by human activities. Certainty has increased 14 percentage points since March 2015, with 51% of the public now "extremely" or "very sure" that global warming is happening. Sixty-two percent of the public now understands that global warming is caused mostly by human activities, an increase of 10 points over that same time period.This report analyzes American's increasing awareness and concern about global warming and its associated risks. Read the report.

March 2019 - On March 1, the City of Miami broke ground for the first Miami Forever Bond Project - the Fairview Flood Mitigation. The project has two phases and is estimated to be completed by early 2020. The first phase is meant to protect against most of the weather events that the city is experiencing right now such as King Tide flooding and dramatic rain events. The second phase is a pump station that will pump between 20,000 and 30,000 gallons a minute.

March 2019 - On March 1, the City of Miami broke ground for the first Miami Forever Bond Project - the Fairview Flood Mitigation. The project has two phases and is estimated to be completed by early 2020. The first phase is meant to protect against most of the weather events that the city is experiencing right now such as King Tide flooding and dramatic rain events. The second phase is a pump station that will pump between 20,000 and 30,000 gallons a minute.

The City of Miami plans to use the Fairview Flood Mitigation project as a means to understand the effectiveness of water outfall back-flow valves and how to best address storm surge and sea-level rise. Watch the Fairview Flood Mitigation Project Groundbreaking.

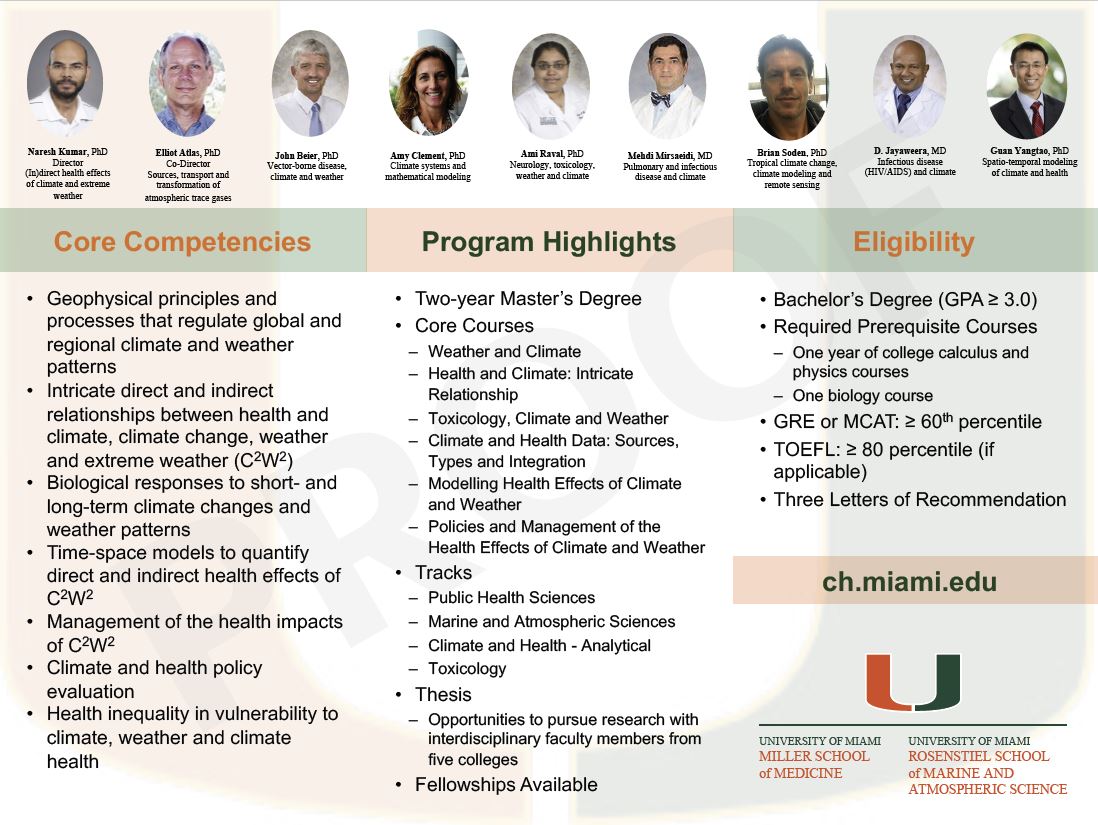

February 2019 (Source: UM) - The University of Miami's Miller School of Medicine and Rosentiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Research (RSMAS) will launch a Master of Science in Climate and Health (U-MSCH) graduate program to begin in Fall 2019. The program will train future generations of professionals, research analysts, planners, decision-makers and leaders to address the intricate relationship between human health and climate, climate change and weather patterns, and weather anomalies, and quantify this relationship at multiple scales ranging from gene expression to individual susceptibility, community response, and the regional morbidity and mortality burden.

February 2019 (Source: UM) - The University of Miami's Miller School of Medicine and Rosentiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Research (RSMAS) will launch a Master of Science in Climate and Health (U-MSCH) graduate program to begin in Fall 2019. The program will train future generations of professionals, research analysts, planners, decision-makers and leaders to address the intricate relationship between human health and climate, climate change and weather patterns, and weather anomalies, and quantify this relationship at multiple scales ranging from gene expression to individual susceptibility, community response, and the regional morbidity and mortality burden.

The two-year program will offer four tracks: Public Health Sciences, Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Climate and Health - Analytical, and Toxicology. Fellowships are available. Click here for more information

Ms. Mikela Pryor, Ms. Janessa Pagan, Ms. Anjali Sharma at the National Technical Association conference in September at Hampton University, VA. Ms. Mikela Pryor, Ms. Janessa Pagan, Ms. Anjali Sharma at the National Technical Association conference in September at Hampton University, VA.

|

(FAMU, Tallahassee, FL) – Summer and Fall 2018 has been productive for the students and faculty in the Biological Systems Engineering program at the College of Agriculture and Food Sciences (CAFS). Ms. Mikela Pryor and Ms. Lesley-Ann Jackson won the 1st place and honorary mention in the poster competition held by sustainability institute at FAMU. Ms. Mikela Pryor, Ms. Janessa Pagan, Ms. Anjali Sharma won the National Technical Association Scholarship to present their work at the conference on September 26-28 at Hampton University, VA, USA 2018. These students were funded by Dr. Aavudai Anandhi's USDA and NSF grants to develop innovative teaching methods to teach abstract, complex concepts in natural resource engineering as well as to train multi-disciplinary graduate students in sustainable Food-Water-Energy nexus. The encouragement and support from students, colleagues, administrators and teaching and learning center is acknowledged.

At the Florida Section American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineering (ASABE) Conference 2018 was held at the Hutchinson Shores Resort, June 13-16 faculty, undergraduate and graduate students were very active. Dr. Aavudai Anandhi Swamy was one of three general session panelists. She spoke about “Environment change, it’s assessment, adaptation and mitigation-an opportunity to utilize the benefits and reduce the harmful effects of change. Ms. Anjali Sharma won 2nd place in the graduate student presentation competition. Her mentor, Dr. Anandhi, was presented with “The Teacher of the Year Award”. Students of the FAMU section of ASABE club presented their work at the conference meeting.

Dr. Anandhi received FAMU’s emerging researcher award 2018. Dr. Anandhi also received the Educational Aids Blue Ribbon Awards at the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineering (ASABE)’s annual international meeting from July 29 – August 1, 2018 at Detroit, Michigan. The blue ribbon award recognizes excellence in informational materials which contribute to the understanding of agricultural and biological engineering subjects. Her innovative teaching method of using Leaf analogy to teach watershed concept won her the blue ribbon award in short publication category.

Dr. Anandhi received FAMU’s emerging researcher award 2018. Dr. Anandhi also received the Educational Aids Blue Ribbon Awards at the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineering (ASABE)’s annual international meeting from July 29 – August 1, 2018 at Detroit, Michigan. The blue ribbon award recognizes excellence in informational materials which contribute to the understanding of agricultural and biological engineering subjects. Her innovative teaching method of using Leaf analogy to teach watershed concept won her the blue ribbon award in short publication category.

Undergraduate and graduate students, in Dr. Anandhi’s group developed a 3-in-1 tool for climate change assessments. This tool could help decision makers plan the best course of action in an altering way. Their evidence-based approach combines three climate research methods to tailor action plans to the needs of a given area: whether that’s an entire country or state, or a single community. This work was published in Ecohydrology journal.

Pictured at left: Dr. Satyanarayan Dev was awarded the Young Engineer Award by the Canadian Society of Bioengineering during the Annual General Meeting on July 25, 2018 at the University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada.

September 2018 (USF, St. Petersburg, FL) - A combination of record-breaking rainfall and inadequate floodplain management led to historic flooding of many coastal cities around the US Gulf of Mexico in 2017. Flooding of developed and built coastal zones is occurring more frequently every year. Many flat, low-lying coastal communities have grown to be large, and residents face high risk of property and financial risk as a changing climate brings higher average sea levels and more frequent extreme storm events every year. Mitigating these risks requires information on coastal topography, vegetation types, and development patterns around coastal cities, for updated flood maps.

Frank Muller-Karger, PhD, Professor at the College of Marine Science of the University of South Florida, has been awarded a National Science Foundation grant ($1,000,000) to establish a Big Data Regional Innovation Hub for a three-year study of these problems in collaboration with Texas A&M University and Google Earth Engine. Dr. Muller-Karger leads a team of researchers that includes Drs. Matt McCarthy, Tim Dixon, graduate students and postdoctoral researchers at USF, James Gibeaut at Texas A&M Corpus Christi, Paul Morin at the University of Minnesota, and Lea Shanley from the South Big Data Hub to update topographic and land cover maps for the entire US Gulf of Mexico coastal plain. Using high-resolution satellite imagery, LiDAR data, and supercomputing resources, the team will update land elevation data and improve land cover maps with a spatial resolution of up to 200 times greater than existing maps at this scale for areas within 50 km of the coast.

Prototype 3-dimensional models will also be developed for the cities of Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Corpus Christi using structure-from-motion (SfM) techniques. Combined with the elevation and land maps, these models will help coastal cities develop plans for sustainable growth while mitigating losses due to flooding, which is forecast to increase with rising sea levels. The maps will be freely available to researchers, managers, and to the general public.

August 2018 (Source:

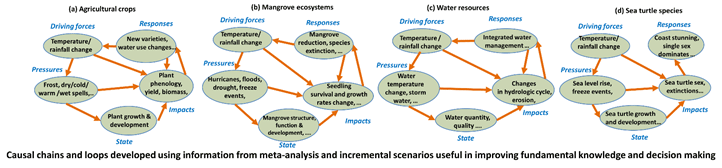

Given the high volume of studies and lines of evidence, and the availability of a number of methods for developing scenarios and the need to develop decision support tools; that developing a tool that combines scenario development and meta-analysis is novel, warranted and timely. Additionally, it would improve the linkages between climate-impacts research and planning, management, adaptation, and mitigation by providing quantitative information to stakeholders and managers.

Florida has many endemic plants, vertebrates, and insects that are only found in Florida and the tropics. Florida’s 2000 miles coastline contains diverse ecosystems and landscapes and habitat for many endangered species. In general, coastal estuaries and bays are of great ecological value and economic significance (produce about 50% of global ecosystem services that benefit humans). Florida’s agriculture yields 63% of the winter vegetables for the U.S. with revenues of $1.48 billion in 1995–1996. Florida is the fourth most populous state in the US and the third fastest growing state, with more than 17% net increase in population from 2000 to 2010. Florida’s biodiversity is threatened by these related stressors including: increasing, land-use change, increasing population and socioeconomic growth. These stressors and play a crucial role in facilitating adaptive change. The close proximity of coastal ecosystems, large human populations, and high productivity make ecosystems in Florida some of the most heavily utilized and threatened on the planet.

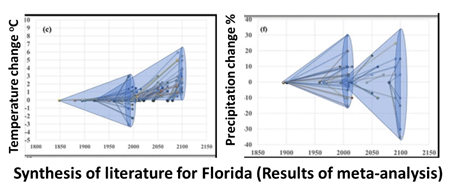

Researchers at FAMU have developed a decision support tool that could reduce the disconnect between the supply and demand for climate information in making decisions from climate change impacts, assessment, of natural and man-made ecosystems. The tool developed by this study has three major components: 1) perform meta-analysis --synthesize and combine recent relevant studies to arrive at conclusions about a body of research on temperature and precipitation changes, 2) develop climate scenario(s) [synthetic or incremental] from meta-analysis, Incremental scenario refers to a method of scenario development where a climatic variable is changed incrementally by arbitrary amounts and 3) development causal chain and loops. Although the developed decision tool is demonstrated by applying it to selected ecosystems and environments in Florida, USA, the tool can be used by multiple stakeholders in ecosystems and environments throughout the world.

Meta-analyses result for Florida: 32 studies revealed precipitation changes ranged between +30% and -40%, while and temperature changes ranged from +6 °C and -3 °C for Florida. Meta-analysis represents a systematic approach to combining the results of relevant studies to arrive at conclusions about, how a body of research has been applied.

Meta-analyses result for Florida: 32 studies revealed precipitation changes ranged between +30% and -40%, while and temperature changes ranged from +6 °C and -3 °C for Florida. Meta-analysis represents a systematic approach to combining the results of relevant studies to arrive at conclusions about, how a body of research has been applied.

Incremental scenarios for Florida: Scenarios must be coherent, internally consistent, and represent plausible descriptions of possible future climate states. From meta-analysis, seven incremental scenarios, were developed at 10% increments in the precipitation change range (+30%, +20%, +10%, -10%, -20%, -30%, -40% precipitation changes) and nine scenarios with 1°C increments in the temperature change range (+6°C, +5°C, +4°C, +3°C, +2°C, +1°C, -1°C, -2°C, -3°C for temperature changes).

The causal chains/loops in Florida (Fig. below) were developed using Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) framework for selected ecosystems and resources (e.g. agro-ecosystem, mangroves, water resources and sea turtles). The meta-analysis in these ecosystems, incremental scenarios as well as author expertise on the topic was used to identify the indicators used to represent the components of the DPSIR framework using chains/loops. The selected ecosystems and resources is impacted due to pressure exerted by the changes in temperature and pressure (incremental scenarios) and their response to them (e.g. mitigation and adaptation strategies) were shown in the causal chains/loops.

Anandhi, A., Sharma, A. and Sylvester, S., 2018. Can meta‐analysis be used as a decision making tool for developing scenarios and causal chains in eco‐hydrological systems?‐Case study in Florida. Ecohydrology, online.

September 2018 (UCF, Tampa, FL) – Many cities across the globe are facing difficult challenges in managing their food, water, and energy systems. The challenges stem from the fact that the issues of food, water, and energy are often tightly connected with each other, not only locally but also globally. This is known as the Food-Water-Energy (FWE) nexus. An effective solution to a local water problem may cause new local problems with food or energy, or cause new water problems at the global level. On a local scale, it is difficult to anticipate whether solutions to one issue in the nexus are sustainable across food, water, and energy systems, both at the local and the global scale. Innovative solutions that encompass the nexus are particularly important to enable cities to better manage their food, water and energy systems and understand the benefits and tradeoffs for different solutions.

September 2018 (UCF, Tampa, FL) – Many cities across the globe are facing difficult challenges in managing their food, water, and energy systems. The challenges stem from the fact that the issues of food, water, and energy are often tightly connected with each other, not only locally but also globally. This is known as the Food-Water-Energy (FWE) nexus. An effective solution to a local water problem may cause new local problems with food or energy, or cause new water problems at the global level. On a local scale, it is difficult to anticipate whether solutions to one issue in the nexus are sustainable across food, water, and energy systems, both at the local and the global scale. Innovative solutions that encompass the nexus are particularly important to enable cities to better manage their food, water and energy systems and understand the benefits and tradeoffs for different solutions.

Ni-Bin Chang, PhD, Professor in the Department of Civil, Environmental Engineering, and Construction Engineering at the University of Central Florida, has been awarded a National Science Foundation (NSF) research grant entitled: “(ENLARGE) Enabling large-scale adaptive integration of technology hubs to enhance community resilience through decentralized urban food-water-energy nexus decision support.” The project aims to generate actionable information by analyzing the distributed production and storage of materials and energy flows into, out of, and within a community/city given their consumption patterns and supply chains associated with various FWE nexuses. This project will develop a multi-scale modeling framework to address the inter-relationship between multiple stressors affecting the food-water-energy nexus in 3 urban environments, Amsterdam, Miami, and Marshall. The models will investigate the impacts of increasing metropolitan populations, rapid land use change, shifting social, economic and governance norms, escalating climate variability, and changing ecosystem services within each of the investigated FWE nexus to elucidate the resultant water, carbon, and ecological footprint for each location. Read more..

Credit: Taylor RA, Ryan SJ, Lippi CA, et al. Predicting the fundamental thermal niche of crop pests and diseases in a changing world: A case study on citrus greening, Journal of Applied Ecology, DOI: 10.1111/1365- 2664.13455

Credit: Taylor RA, Ryan SJ, Lippi CA, et al. Predicting the fundamental thermal niche of crop pests and diseases in a changing world: A case study on citrus greening, Journal of Applied Ecology, DOI: 10.1111/1365- 2664.13455