Headline News Archive

September 29, 2017 (Source: FSU) - New research from a team of Florida State University scientists and their collaborators is helping to explain the link between a changing global climate and a dramatic decline in bumble bee populations worldwide.

September 29, 2017 (Source: FSU) - New research from a team of Florida State University scientists and their collaborators is helping to explain the link between a changing global climate and a dramatic decline in bumble bee populations worldwide.

In a study published Friday, Sept. 29, in the journal Ecology Letters, researchers examining three subalpine bumble bee species in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains found that, for some bumble bees, a changing climate means there just aren’t enough good flowers to go around.

The team analyzed the bees’ responses to direct and indirect climate change effects.

“Knowing whether climate variation most affects bumble bees directly or indirectly will allow us to better predict how bumble bee populations will cope with continued climate change,” said FSU postdoctoral researcher Jane Ogilvie, the study’s lead investigator. “We found that the abundances of all three bumble bee species were mostly affected by indirect effects of climate on flower distribution through a season.”

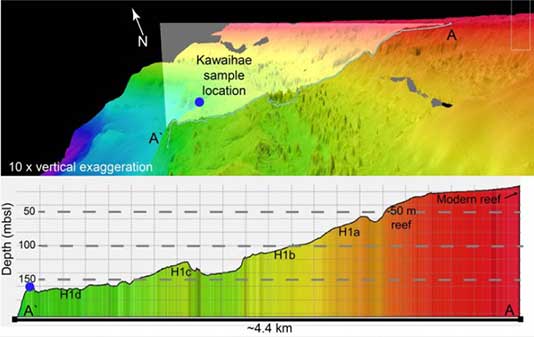

September 28, 2017 (Source: University of Sydney/Science Daily) - Investigations to predict changes in sea levels and their impacts on coastal systems are a step closer, as a result of international collaboration between the University of Sydney and researchers from Japan, Spain, and the United States.

Scientists globally are investigating just how quickly sea-level rise can occur as a result of global warming and ice sheets melting.

Recent findings suggest that episodes of very rapid sea-level rise of about 20m in less than 500 years occurred in the last deglaciation, caused by periods of catastrophic ice-sheet collapse as Earth warmed after the last ice age about 20,000 years ago.

Lead author, PhD candidate at the University of Sydney, Kelsey Sanborn, has shown this sea-level rise event was associated with "drowning" or death of coral reefs in Hawaii.

The research was a collaborative effort between the University of Sydney, the University of Tokyo, the University of Florida, the University of Granada, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, the University of Hawaii, and the Association for Marine Exploration.

September 21, 2017 (Source: FIU) - A team of researchers headed by FIU College of Business professor Shahid Hamid, using the Florida Public Hurricane Loss Model, estimates that Hurricane Irma caused $19.4 billion in wind-related losses to Florida residents alone. The data doesn’t cover flood losses.

Of that total, $6.3 billion will be paid by insurance companies. As a result, roughly two-thirds of the losses will be borne by homeowners. The highest wind losses are in Lee County (Fort Myers and Cape Coral), followed by Collier County (Naples, Marco Island and Immokalee).

Hamid’s team includes specialists in meteorology, storm surge, hydrology, engineering, finance and actuarial science, computer science and statistics from FIU as well as the University of Florida, Florida State University, Florida Institute of Technology, University of Miami and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

September 11, 2017 (Source: University of Bonn) - The East Coast of the United States is threatened by more frequent flooding in the future. This is shown by a recent study by the Universities of Bonn, South Florida, and Rhode Island. According to this, the states of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina are most at risk. Their coastal regions are being immersed by up to three millimeters per year – among other things, due to human intervention. The work is published in the journal Scientific Reports by the Nature Publishing Group.

Cities such as Miami on the East Coast of the USA are being affected by flooding more and more frequently. The causes are often not hurricanes with devastating rainfall such as Katrina, or the recent hurricanes Harvey or Irma. On the contrary: flooding even occurs on sunny, relatively calm days. It causes damage to houses and roads and disrupts traffic, yet does not cost any people their lives. It is thus also known as ‘nuisance flooding’.

And this nuisance is set to occur much more frequently in the future. At least researchers from the Universities of Bonn, South Florida, and Rhode Island are convinced of this. The international team evaluated data from the East Coast of America, including GPS and satellite measurements. These show that large parts of the coastal region are slowly yet steadily sinking into the Atlantic Ocean.

“There are primarily two reasons for this phenomenon,” explains Makan A. Karegar from the University of South Florida, currently a guest researcher at the Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformation at the University of Bonn. “During the last ice age around 20,000 years ago, large parts of Canada were covered by an ice sheet. This tremendous mass pressed down on the continent.” Some areas of the earth’s mantle were thus pressed sideways under the ice, causing the coastal regions that were free of ice to be raised. “When the ice sheet then melted, this process was reversed,” explains Karegar. “The East Coast has thus been sinking back down for the last few thousand years.”

August 30, 2017 - Joseph Smoak (USF), Brad Rosenheim (USF College of Marine Science), Ryan Moyer and Kara Radabaugh (Florida Fish & Wildlife Research Institute), Lisa Chambers (University of Central Florida), and David Lagomasino (University of Maryland) have been award a $1.33 million grant from the United States Department of Agriculture to study “Blue Carbon” ecosystems along the South Florida coast. Blue Carbon is a term used to describe carbon captured in the ocean and coastal ecosystems. The goal of the project is to measure and map carbon stored in the coastal wetlands of South Florida and predict how these stores of carbon will change under the influence of climate change and anthropogenic pressures. The collection of the data involves field sampling in the wetlands, the use of NASA fixed wing aircraft and satellite imagery.

Grant title: Organic carbon biomass, burial, and biogeochemistry in blue carbon ecosystems along the South Florida coast: climate change and anthropogenic influences

August 17, 2017 (Source: UM/RSMAS) - Predicting the weather three to four weeks in advance is extremely challenging, yet many critical decisions affecting communities and economies must be made using this lead time. However, model forecasts available for the first time this week could help NOAA’s operational Climate Prediction Center (CPC) significantly improve its week 3-4 temperature and precipitation outlooks for the U.S.

The Subseasonal Experiment (SubX) is a two year project, led by University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science atmospheric scientist Ben Kirtman, that combines multiple global models from NOAA, NASA, Environment Canada, the Navy, and National Center for Atmospheric Research to produce once-a-week real-time experimental forecasts as well as a set of forecasts for past dates, called reforecasts, now available to both CPC and the research community.

“The multi-model reforecasts perfectly dovetail with the real-time forecasts so that you can perform a robust calibration and skill assessment,” said Ben Kirtman, lead of the SubX project team and University of Miami Rosenstiel School atmospheric scientist. “The research you do can immediately translate into potential improvements of an operational product, and that’s really exciting.”

FIU Marine Ecologist James Fourqurean Elected President of Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation

August 15, 2017 (Source: FIU) - FIU marine ecologist James Fourqurean has been elected president of the Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation. Fourqurean will lead the organization, which is comprised of people who study and manage estuaries, with a plan to educate public officials about coastal science and resilience in a changing climate.

August 15, 2017 (Source: FIU) - FIU marine ecologist James Fourqurean has been elected president of the Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation. Fourqurean will lead the organization, which is comprised of people who study and manage estuaries, with a plan to educate public officials about coastal science and resilience in a changing climate.

“Distrust of scientists seems to be at an all-time high when scientific understanding is really important to help us face the coming challenges of a changing environment,” said Fourqurean, director of FIU’s Marine Education and Research Initiative. “I hope to ease the dialog between elected officials and scientists so we can share ideas to ensure a better future.”

August 11, 2017 (Source: FL DEP) - The Florida Department of Environmental Protection, in partnership with the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) and Nova Southeastern University (NSU), has modified the Port of Miami Anchorage Area in Miami Beach. Changes in design and configuration will protect more than 600 acres of coral reef from future impacts by keeping boats from protected reef areas. The anchorage area, where boats can safely maneuver and park, will now be divided into two separate areas, including an inner western anchorage for smaller vessels and an outer eastern anchorage for larger vessels totaling 1.5 square nautical miles.

"This outstanding conservation management achievement is a testament to how local stakeholders can effectively work together to protect Florida's ecologically and economically important coral reefs," said Joanna Walczak, Southeast regional administrator for DEP's Florida Coastal Office.

The new anchorages are the result of extensive collaboration between numerous stakeholder groups, agencies, universities and private citizens at federal, state and local levels. Studies conducted by DEP and NSU showed that anchorage modification was necessary to reduce reef damage to the ecologically and economically important northern portion of the Florida Reef Tract. This study led to the formation of a working group coordinated by USCG, DEP and NSU, where a group of varied stakeholders including federal and state agencies, port pilots, Port Miami administration, university scientists and other shipping interests worked together to design the new configuration.

August 9, 2015 (Source: UF) - Sea level rise hot spots -- bursts of accelerated sea rise that last three to five years -- happen along the U.S. East Coast thanks to a one-two punch from naturally occurring climate variations, a new University of Florida study shows.

August 9, 2015 (Source: UF) - Sea level rise hot spots -- bursts of accelerated sea rise that last three to five years -- happen along the U.S. East Coast thanks to a one-two punch from naturally occurring climate variations, a new University of Florida study shows.

After UF scientists identified a hot spot reaching from Cape Hatteras to Miami, they probed the causes by analyzing tidal and climate data for the U.S. eastern seaboard. The new study, published online today in Geophysical Research Letters, shows that seas rose in the southeastern U.S. between 2011 and 2015 by more than six times the global average sea level rise that is already happening due to human-induced global warming.

The study's findings suggest that future sea level rise resulting from global warming will also have these hot spot periods superimposed on top of steadily rising seas, said study co-author Andrea Dutton, assistant professor in UF's department of geological sciences in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

"The important point here is that smooth projections of sea level rise do not capture this variability, so adverse effects of sea level rise may occur before they are predicted to happen," Dutton said. "The entire U.S. Atlantic coastline is vulnerable to these hot spots that may amplify the severity of coastal flooding."

UF News Release

August 9, 2017 (Source: FSU) - A 94-million-year-old climate change event that severely imperiled marine organisms may provide some unnerving insights into long-term trends in our modern oceans, according to a Florida State University researcher.

August 9, 2017 (Source: FSU) - A 94-million-year-old climate change event that severely imperiled marine organisms may provide some unnerving insights into long-term trends in our modern oceans, according to a Florida State University researcher.

In a study published today in the journal Science Advances, Assistant Professor of Geology Jeremy Owens traces a 50,000-year period of ocean deoxygenation preceding an ancient climate event that dramatically disturbed global ocean chemistry and led to the extinction of many marine organisms. He also draws parallels to similar rates of oxygen depletion observed in our contemporary oceans.

“We found that before this major shift in the climate, there was a stretch of oxygen depletion of about 50,000 years,” Owens said. “The rate of deoxygenation during that time is somewhat equivalent to the rate at which many scientists suggest we’re losing oxygen from our oceans today.”

August 7, 2017 (Source: FIU) - Scientists are zeroing in on the seagrass meadows that could help slow down climate change. Seagrass meadows are great absorbers of carbon dioxide from the air. But the algae, animals, corals and plants that live among them release large amounts of carbon dioxide, according to newly released research. The scientists are now identifying seagrass locations with fewer emitters to target for conservation. Scientists at Florida International University examined seagrass meadows in Florida Bay, some of the largest on Earth, where waters are warm and plant and animal abundance is high. They compared these ecosystems to those in southeastern Brazil where meadows are smaller, waters are cooler, and plant and animal abundance is lower. They found that although Florida Bay’s seagrasses act as carbon sinks, the organisms living among them offset the benefits of seagrass carbon storage by releasing carbon dioxide.

August 7, 2017 (Source: FIU) - Scientists are zeroing in on the seagrass meadows that could help slow down climate change. Seagrass meadows are great absorbers of carbon dioxide from the air. But the algae, animals, corals and plants that live among them release large amounts of carbon dioxide, according to newly released research. The scientists are now identifying seagrass locations with fewer emitters to target for conservation. Scientists at Florida International University examined seagrass meadows in Florida Bay, some of the largest on Earth, where waters are warm and plant and animal abundance is high. They compared these ecosystems to those in southeastern Brazil where meadows are smaller, waters are cooler, and plant and animal abundance is lower. They found that although Florida Bay’s seagrasses act as carbon sinks, the organisms living among them offset the benefits of seagrass carbon storage by releasing carbon dioxide.

“In seagrass meadows, these two processes happen simultaneously and have opposite effects on carbon sequestration,” said Jason Howard, researcher in FIU’s Marine Education Research Initiative and lead author of the study. “If we want to mitigate the most carbon dioxide emissions, we need to understand these competing processes and choose conservation sites accordingly.”

August 1, 2017 (Source: FSU) - There could be some good news on the horizon as scientists try to understand the effects and processes related to climate change. A team of Florida State University scientists has discovered that chemical weathering, a process in which carbon dioxide breaks down rocks and then gets trapped in sediment, can happen at a much faster rate than scientists previously assumed and could potentially counteract some of the current and future climate change caused by humans. The findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

August 1, 2017 (Source: FSU) - There could be some good news on the horizon as scientists try to understand the effects and processes related to climate change. A team of Florida State University scientists has discovered that chemical weathering, a process in which carbon dioxide breaks down rocks and then gets trapped in sediment, can happen at a much faster rate than scientists previously assumed and could potentially counteract some of the current and future climate change caused by humans. The findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Scientists have generally thought that this process takes hundreds of thousands to millions of years to occur, helping to alleviate warming trends at an exceptionally slow rate. Rather than potentially millions of years, FSU researchers now suggest it can take several tens of thousands of years. It’s not a quick fix though. “Increased chemical weathering is one of Earth’s natural responses to carbon dioxide increases,” said Theodore Them, the lead researcher on the paper and a postdoctoral researcher at Florida State and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. “The good news is that this process can help balance the effects of fossil fuel combustion, deforestation and agricultural practices. The bad news is that it will not begin to counteract the excessive amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide that humans are emitting for at least several thousand years.”

July 31, 2017 (Source: FIT) - Occurrences of three common diseases affecting Caribbean corals spike during El Niño years, an alarming association given how climate change may boost the intensity of El Niños. The findings from Florida Institute of Technology research associate Carly Randall and biology professor Rob van Woesik, published earlier this month in the journal Scientific Reports, are based on an analysis of 18 years of coral-disease data, at nearly 2,100 sites collected by the Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment Program. Those data were compared with 18 years of coinciding climate data to see if the disease cycles matched the climate cycles. “We found that three coral diseases – white-band disease, yellow-band disease and dark-spot syndrome – peak every 2-4 years, and that they share common periodicities with El Niño cycles,” Randall said. “Our results indicate that coral diseases cycle predictably and that they often correspond with El Niño.”

July 31, 2017 (Source: FIT) - Occurrences of three common diseases affecting Caribbean corals spike during El Niño years, an alarming association given how climate change may boost the intensity of El Niños. The findings from Florida Institute of Technology research associate Carly Randall and biology professor Rob van Woesik, published earlier this month in the journal Scientific Reports, are based on an analysis of 18 years of coral-disease data, at nearly 2,100 sites collected by the Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment Program. Those data were compared with 18 years of coinciding climate data to see if the disease cycles matched the climate cycles. “We found that three coral diseases – white-band disease, yellow-band disease and dark-spot syndrome – peak every 2-4 years, and that they share common periodicities with El Niño cycles,” Randall said. “Our results indicate that coral diseases cycle predictably and that they often correspond with El Niño.”

July 25, 2017 (Source: UM/RSMAS) - A new study found that Caribbean staghorn corals (Acropora cervicornis) are benefiting from “coral gardening,” the process of restoring coral populations by planting laboratory-raised coral fragments on reefs. The research, led by scientists at the University of Miami, Nova Southeastern University, and additional partners, has important implications for the long-term survival of coral reefs worldwide, which have been in worldwide decline from multiple stressors such as climate change and ocean pollution.

July 25, 2017 (Source: UM/RSMAS) - A new study found that Caribbean staghorn corals (Acropora cervicornis) are benefiting from “coral gardening,” the process of restoring coral populations by planting laboratory-raised coral fragments on reefs. The research, led by scientists at the University of Miami, Nova Southeastern University, and additional partners, has important implications for the long-term survival of coral reefs worldwide, which have been in worldwide decline from multiple stressors such as climate change and ocean pollution.

“Our study showed that current restoration methods are very effective,” said UM Rosenstiel school coral biologist Stephanie Schopmeyer, the lead author of the study. “Healthy coral reefs are essential to our everyday life and successful coral restoration has been proven as a recovery tool for lost coastal resources.”

July 19, 2017 (Source: FSU) - For more than a decade, people have used social media to express themselves and inform and engage users across the globe. Now, a new study by Florida State University researchers examines the impact rising temperatures have on Twitter activity, and how government officials use the social media tool to warn the general public of heatwave conditions.

July 19, 2017 (Source: FSU) - For more than a decade, people have used social media to express themselves and inform and engage users across the globe. Now, a new study by Florida State University researchers examines the impact rising temperatures have on Twitter activity, and how government officials use the social media tool to warn the general public of heatwave conditions.

FSU doctoral student Jihoon Jung and Assistant Professor of Geography Chris Uejio co-authored the paper published this month in the International Journal of Biometeorology. They found in Atlanta, Los Angeles and New York City that as temperatures rose, the number of temperature-related tweets increased.

“If more agencies start to include social media and tap into what people are actually experiencing in real time, they can improve their extreme heat early warning systems,” Uejio said. “We are also hoping that these government groups will start to include more health information in their social media messaging.”

July 14, 2017 (Source: FSU) - Scientists have long believed that the waters of the Central and Northeast Pacific Ocean were inhospitable to deep-sea scleractinian coral, but a Florida State University professor’s discovery of an odd chain of reefs suggests there are mysteries about the development and durability of coral colonies yet to be uncovered. Associate Professor of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science Amy Baco-Taylor, in collaboration with a team from Texas A&M University, observed these reefs during an autonomous underwater vehicle survey through the seamounts of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

July 14, 2017 (Source: FSU) - Scientists have long believed that the waters of the Central and Northeast Pacific Ocean were inhospitable to deep-sea scleractinian coral, but a Florida State University professor’s discovery of an odd chain of reefs suggests there are mysteries about the development and durability of coral colonies yet to be uncovered. Associate Professor of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science Amy Baco-Taylor, in collaboration with a team from Texas A&M University, observed these reefs during an autonomous underwater vehicle survey through the seamounts of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

In an article published today in the journal Scientific Reports, Baco-Taylor and her team document these reefs and discuss possible explanations for their appearance in areas considered impossibly hostile to reef-forming scleractinia, whose communities are formed by small, stony polyps that settle on the seabed and grow bony skeletons to protect their soft bodies. If there are additional reefs sprinkled across the Northwestern Hawaiian seamounts, Baco-Taylor wants to find them. Further study of these reefs could reveal important secrets about how these organisms might endure in the age of climbing carbon dioxide levels and ocean acidification. “If more of these reefs are there, that would run counter to what ocean acidification and carbonate chemistry dictates,” Baco-Taylor said. “It leaves us with some big questions: Is there something that we’re not understanding? How is this possible?”

July 7, 2017 (Source: UCF) - Improving projections for how much ocean levels may change in the future and what that means for coastal communities has vexed researchers studying sea level rise for years, but a new international study that incorporates extreme events may have just given researchers and coastal planners what they need.

July 7, 2017 (Source: UCF) - Improving projections for how much ocean levels may change in the future and what that means for coastal communities has vexed researchers studying sea level rise for years, but a new international study that incorporates extreme events may have just given researchers and coastal planners what they need.

The study, published today in Nature Communications uses newly available data and advanced models to improve global predictions when it comes to extreme sea levels. The results suggest that extreme sea levels will likely occur more frequently than previously predicted, particularly in the west coast regions of the U.S. and in large parts of Europe and Australia.

“Storm surges globally lead to considerable loss of life and billions of dollars of damages each year, and yet we still have a limited understanding of the likelihood and associated uncertainties of these extreme events both today and in the future,” said Thomas Wahl, an assistant engineering professor in the University of Central Florida who led the study.

June 20, 2017 (Source: FAU) - Rain or shine has new meaning thanks to an innovative, inexpensive and simple tactic developed by researchers at Florida Atlantic University that will really change how people think about watering their lawns. The tactic? A straightforward road sign.

June 20, 2017 (Source: FAU) - Rain or shine has new meaning thanks to an innovative, inexpensive and simple tactic developed by researchers at Florida Atlantic University that will really change how people think about watering their lawns. The tactic? A straightforward road sign.

Outdoor water restrictions are a common water conservation strategy in the United States, Canada, Australia and other countries to address water use as it relates to maintaining lawns and greenspace. In fact, 29 states in the U.S. have outdoor water restrictions that only allow lawn watering on certain days or times. Conserving water is critical because 50 to 90 percent of household water is used for this purpose. Furthermore, to provide each South Florida lawn with the necessary one-inch of water per week, it takes more than 62 gallons of water for every 10-foot-by-10-foot area.

However, this one-pronged approach of water restrictions that involves pre-set and arbitrary lawn-watering schedules does not always result in actual water savings so Tara Root, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Geosciences in FAU’s Charles E. Schmidt College of Science, and Felicia D. Survis, who recently earned her Ph.D. at FAU, decided to do some research.

For two years, which included two annual wet and dry seasons, they conducted a unique study in Wellington, a suburban village in South Florida, to demonstrate how you can save a lot of water by simply providing people with more information than just directives, schedules or guidelines about which days of the week they can water their lawns. Wellington provided the perfect venue for this study since the village is located in a region that has distinct wet and dry seasons and that is subject to permanent year-round mandatory water restrictions. Additionally, Wellington was interested in the research and helped to implement the pilot program. Results of their study are published in the current issue of the Journal of Environmental Management.

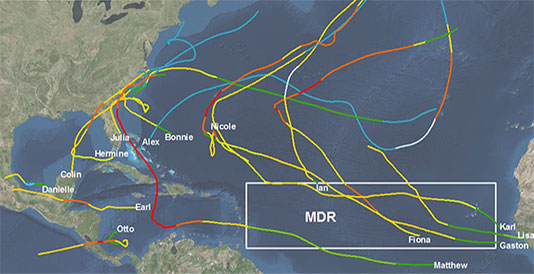

June 1, 2017 (Source: USF) - The 2016 hurricane season was the longest hurricane season since 1951, making it the second-longest hurricane season on record. That’s the conclusion drawn in a paper just published in Geophysical Research Letters. Lead author Jennifer Collins, PhD, associate professor in the School of Geosciences at the University of South Florida, writes: “Overall 2016 was notable for a series of extremes, some rarely and a few never before observed in the Atlantic basin, a potential harbinger of seasons to come in the face of ongoing global climate change.” The study examines 15 tropical storms, seven hurricanes and three intense hurricanes. The season was slightly above average when considering Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) uses to measure cyclonic activity.

June 1, 2017 (Source: USF) - The 2016 hurricane season was the longest hurricane season since 1951, making it the second-longest hurricane season on record. That’s the conclusion drawn in a paper just published in Geophysical Research Letters. Lead author Jennifer Collins, PhD, associate professor in the School of Geosciences at the University of South Florida, writes: “Overall 2016 was notable for a series of extremes, some rarely and a few never before observed in the Atlantic basin, a potential harbinger of seasons to come in the face of ongoing global climate change.” The study examines 15 tropical storms, seven hurricanes and three intense hurricanes. The season was slightly above average when considering Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) uses to measure cyclonic activity.