Headline News Archive

July 3, 2018 (Source: GSA) - Geological Society Fellowship is an honor bestowed on the best of the profession by election at the spring GSA Council meeting. GSA members are nominated by existing GSA Fellows in recognition of their distinguished contributions to the geosciences through such avenues as publications, applied research, teaching, administration of geological programs, contributing to the public awareness of geology, leadership of professional organizations, and taking on editorial, bibliographic, and library responsibilities.

Ellen E. Martin (University of Florida)

Ellen E. Martin (University of Florida)

"Ellen has an impressive combination of a distinguished research program

in addition to an assiduous dedication to mentoring and leadership within

her department, university, and international scientific community."

—Andrea Dutton

Michael C. Sukop (Florida International University).

Michael C. Sukop (Florida International University).

"Dr. Sukop's nomination is for his outstanding research publications and service

to the GSA Hydrogeology Division. His research includes using Lattice Boltzman

Modeling for investigating complex hydrogeological processes, such as multi-phase flow,

movement of droplets, and flow in karst. Dr. Sukop also investigates water management and coastal flooding in Florida." —Larry McKay

GSA’s newly elected Fellows will be recognized at the GSA 2018 Annual Meeting & Exposition Presidential Address & Awards Ceremony on 4 Nov. in Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

June 11, 2018 (Source: FSU) - Global climate change, fueled by skyrocketing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, is siphoning oxygen from today’s oceans at an alarming pace — so fast that scientists aren’t entirely sure how the planet will respond. Their only hint? Look to the past. In a study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from Florida State University did just that — and what they found brings into stark relief the disastrous effects a deoxygenated ocean could have on marine life. Millions of years ago, scientists discovered, powerful volcanoes pumped Earth’s atmosphere full of carbon dioxide, draining the oceans of oxygen and driving a mass extinction of marine organisms.“We want to understand how volcanism, which can be related to modern anthropogenic carbon dioxide release, manifests itself in ocean chemistry and extinction events,” said study co-author Jeremy Owens, an assistant professor in FSU’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science. “Could this be a precursor to what we’re seeing today with oxygen loss in our oceans? Will we experience something as catastrophic as this mass extinction event?”

June 11, 2018 (Source: FSU) - Global climate change, fueled by skyrocketing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, is siphoning oxygen from today’s oceans at an alarming pace — so fast that scientists aren’t entirely sure how the planet will respond. Their only hint? Look to the past. In a study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from Florida State University did just that — and what they found brings into stark relief the disastrous effects a deoxygenated ocean could have on marine life. Millions of years ago, scientists discovered, powerful volcanoes pumped Earth’s atmosphere full of carbon dioxide, draining the oceans of oxygen and driving a mass extinction of marine organisms.“We want to understand how volcanism, which can be related to modern anthropogenic carbon dioxide release, manifests itself in ocean chemistry and extinction events,” said study co-author Jeremy Owens, an assistant professor in FSU’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science. “Could this be a precursor to what we’re seeing today with oxygen loss in our oceans? Will we experience something as catastrophic as this mass extinction event?”

May 31, 2018 (Source: FIU) - Jayantha Obeysekera has been named director of the FIU Sea Level Solutions Center. He will lead the research, education and outreach hub designed to develop and implement solutions for the impacts caused by one of the greatest threats facing Florida today — rising seas. Founding Director Tiffany Troxler has been named director of science. As director, Obeysekera will focus on developing national and international collaborations, expanding research initiatives and assisting local and regional governments with adaptation and resilience. The center is a key program in FIU’s Institute of Water and Environment. “The Sea Level Solutions Center at FIU has a tremendous potential to be a national center of excellence for sea level rise research,” Obeysekera said. “It is a hub where expert faculty and students at FIU can collaborate with national and international partners to build resiliency to communities in South Florida and elsewhere.”

May 31, 2018 (Source: FIU) - Jayantha Obeysekera has been named director of the FIU Sea Level Solutions Center. He will lead the research, education and outreach hub designed to develop and implement solutions for the impacts caused by one of the greatest threats facing Florida today — rising seas. Founding Director Tiffany Troxler has been named director of science. As director, Obeysekera will focus on developing national and international collaborations, expanding research initiatives and assisting local and regional governments with adaptation and resilience. The center is a key program in FIU’s Institute of Water and Environment. “The Sea Level Solutions Center at FIU has a tremendous potential to be a national center of excellence for sea level rise research,” Obeysekera said. “It is a hub where expert faculty and students at FIU can collaborate with national and international partners to build resiliency to communities in South Florida and elsewhere.”

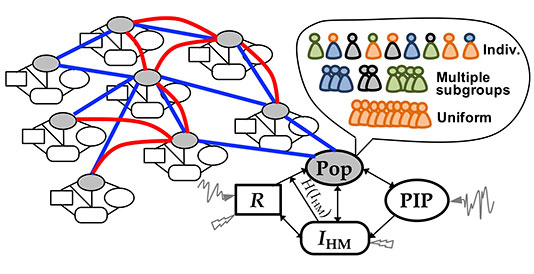

May 30, 2018 (Source: UF/ABE) - Researchers from the University of Florida, Columbia University, and East Carolina University have been awarded a grant from the US Department of Defense for a project titled, "Towards a Multi-Scale Theory on Coupled Human Mobility and Environmental Change." The project will be led by Rachata Muneepeerakul from UF's Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. The results of this project will provide interested DoD entities an enhanced ability to anticipate and predict population movements resulting from environmental changes, including a development of a more effective migration early warning system. Such ability will help foster better logistical responses on the part of DoD to any given event or sets of events.

May 30, 2018 (Source: UF/ABE) - Researchers from the University of Florida, Columbia University, and East Carolina University have been awarded a grant from the US Department of Defense for a project titled, "Towards a Multi-Scale Theory on Coupled Human Mobility and Environmental Change." The project will be led by Rachata Muneepeerakul from UF's Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. The results of this project will provide interested DoD entities an enhanced ability to anticipate and predict population movements resulting from environmental changes, including a development of a more effective migration early warning system. Such ability will help foster better logistical responses on the part of DoD to any given event or sets of events.

May 29, 2018 (Source: Jack Putz) - A recently published paper in Global Change Biology discusses how tropical forests provide critical ecosystem services for life on Earth including climate protection by storing large amounts of carbon. One big challenge is that these forests are located in poor countries where improvement of human livelihoods is paramount. The study, led by researchers from Boise State University, sheds light on how to balance timber production and carbon storage in tropical forests. The researchers used field data and mathematical models to determine thresholds for logging intensity, after which tropical forests managed for timber begin to lose their ability to recover their carbon stocks and supply timber. The focus on timber stand management is warranted by the fact that half of all remaining tropical forests are being logged.

May 29, 2018 (Source: Jack Putz) - A recently published paper in Global Change Biology discusses how tropical forests provide critical ecosystem services for life on Earth including climate protection by storing large amounts of carbon. One big challenge is that these forests are located in poor countries where improvement of human livelihoods is paramount. The study, led by researchers from Boise State University, sheds light on how to balance timber production and carbon storage in tropical forests. The researchers used field data and mathematical models to determine thresholds for logging intensity, after which tropical forests managed for timber begin to lose their ability to recover their carbon stocks and supply timber. The focus on timber stand management is warranted by the fact that half of all remaining tropical forests are being logged.

The study was based on over two decades of data from Guyana, a biodiverse country that is globally important as a forest carbon reservoir. The results provide novel insights into logging practices compatible with maintenance of the carbon and timber values of these forests. The researchers found that recovery rates of forests after logging, even with the application of the highest standards of logging practices known as reduced-impact logging (RIL), depends on the presence of old growth. Overall, the benefits of RIL diminish at high logging intensities. An additional experimental treatment, the liberation from competition of small commercial trees, successfully increased timber yields but the forest stored 20% less carbon.

Professor Jack Putz from the University of Florida, the senior collaborator on the study, pointed out major challenges for tropical forest management are identification of logging intensity thresholds and development of post-harvest treatments that are compatible with maintenance of ecosystem services. “Our study highlights the importance of remnant old-growth trees and the consequences of management intensification. Success at intensification may allow forest managers to meet societal needs for timber in smaller areas, albeit at the cost of other ecosystem services such as carbon and biodiversity in these areas. But intensification may also spare more pristine forests from disturbances associated with logging.”

May 8, 2018 (Source: UNC/ScienceDaily) - New research found that most marine life in Marine Protected Areas will not be able to tolerate warming ocean temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions. The study found that with continued 'business-as-usual' emissions, the protections currently in place won't matter, because by 2100, warming and reduced oxygen concentration will make Marine Protected Areas uninhabitable by most species currently residing in those areas. "There has been a lot of talk about establishing marine reserves to buy time while we figure out how to confront climate change," said Rich Aronson, ocean scientist at Florida Institute of Technology and a researcher on the study. "We're out of time, and the fact is we already know what to do: We have to control greenhouse gas emissions."

May 8, 2018 (Source: UNC/ScienceDaily) - New research found that most marine life in Marine Protected Areas will not be able to tolerate warming ocean temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions. The study found that with continued 'business-as-usual' emissions, the protections currently in place won't matter, because by 2100, warming and reduced oxygen concentration will make Marine Protected Areas uninhabitable by most species currently residing in those areas. "There has been a lot of talk about establishing marine reserves to buy time while we figure out how to confront climate change," said Rich Aronson, ocean scientist at Florida Institute of Technology and a researcher on the study. "We're out of time, and the fact is we already know what to do: We have to control greenhouse gas emissions."

April 30, 2018 (Source: FIU) - Mangroves running for their lives may have just hit the end of the road. The problem is so clear, it might be the first real sign Earth has entered a new geological era. Using a combination of aerial photographs from the 1930s, modern satellite imagery and ground sediment samples, FIU Sea Level Solutions Center researchers Randall W. Parkinson and John F. Meeder tracked the mangroves’ westward retreat from the coastal Everglades. Now, their backs are to the wall – literally. Having reached the L-31E levee in southeast Miami-Dade County, there’s nowhere left for mangroves in that part of the Everglades to flee. "You can see migration westward has stopped right where that levee is," Parkinson said. "In many cases there no space for them to migrate into — there’s development or some feature that blocks their migration. They’re done. That’s it."

April 30, 2018 (Source: FIU) - Mangroves running for their lives may have just hit the end of the road. The problem is so clear, it might be the first real sign Earth has entered a new geological era. Using a combination of aerial photographs from the 1930s, modern satellite imagery and ground sediment samples, FIU Sea Level Solutions Center researchers Randall W. Parkinson and John F. Meeder tracked the mangroves’ westward retreat from the coastal Everglades. Now, their backs are to the wall – literally. Having reached the L-31E levee in southeast Miami-Dade County, there’s nowhere left for mangroves in that part of the Everglades to flee. "You can see migration westward has stopped right where that levee is," Parkinson said. "In many cases there no space for them to migrate into — there’s development or some feature that blocks their migration. They’re done. That’s it."

April 16, 2018 (Source: UF) - University of Florida history professor Jack E. Davis is the winner of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in History for his book “The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea,” the Pulitzer Prize Board announced today. “The Gulf” also won the Kirkus Prize, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, was a New York Times Notable Book, and made a number of other “best of” lists in national publications. When Davis first conceived of “The Gulf,” the Deepwater Horizon accident that dumped 130 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico had not yet happened. That Davis was writing a history of the Gulf around the same time as the largest oil spill in history was coincidental, and allowed him to focus on aspects other than the spill, which he says, “seemed to rob the Gulf of Mexico of its true identity. I wanted to restore it, to show people that the Gulf is more than an oil spill,” he said. “It’s got a rich, natural history connected to Americans, and it’s not integrated into the larger American historical narrative. That’s a wrong I wanted to correct.”

April 16, 2018 (Source: UF) - University of Florida history professor Jack E. Davis is the winner of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in History for his book “The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea,” the Pulitzer Prize Board announced today. “The Gulf” also won the Kirkus Prize, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, was a New York Times Notable Book, and made a number of other “best of” lists in national publications. When Davis first conceived of “The Gulf,” the Deepwater Horizon accident that dumped 130 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico had not yet happened. That Davis was writing a history of the Gulf around the same time as the largest oil spill in history was coincidental, and allowed him to focus on aspects other than the spill, which he says, “seemed to rob the Gulf of Mexico of its true identity. I wanted to restore it, to show people that the Gulf is more than an oil spill,” he said. “It’s got a rich, natural history connected to Americans, and it’s not integrated into the larger American historical narrative. That’s a wrong I wanted to correct.”

April 9, 2018 (Source: FSU) - New research from Florida State University scientists has found that urban areas throughout the Florida peninsula are experiencing shorter, increasingly intense wet seasons relative to underdeveloped or rural areas.

April 9, 2018 (Source: FSU) - New research from Florida State University scientists has found that urban areas throughout the Florida peninsula are experiencing shorter, increasingly intense wet seasons relative to underdeveloped or rural areas.

The study, published in the Nature Partner Journal Climate and Atmospheric Science, provides new insight into the question of land development’s effect on seasonal climate processes.

Using a system that indexed urban land cover on a scale of one to four — one being least urban and four being most urban — the researchers mapped the relationship between land development and length of wet season.

“What we found is a trend of decreasing wet-season length in Florida’s urban areas compared to its rural areas,” said Vasu Misra, associate professor of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science and lead investigator of the study.

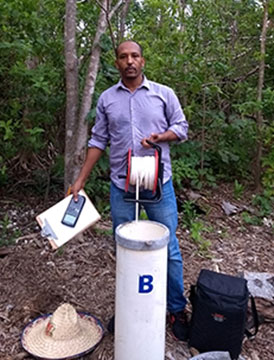

March 30, 2018 (Source: FIU) - Small-scale droughts can have big effects on the Florida Everglades. Ph.D. student Anteneh Abiy is digging deep into these abnormally low rainfall events. He doesn’t have to do go too far into weather data to begin his work. 2017 was drier than usual. The Everglades received 6 inches of rainfall less than the annual average.

March 30, 2018 (Source: FIU) - Small-scale droughts can have big effects on the Florida Everglades. Ph.D. student Anteneh Abiy is digging deep into these abnormally low rainfall events. He doesn’t have to do go too far into weather data to begin his work. 2017 was drier than usual. The Everglades received 6 inches of rainfall less than the annual average.

Fresh water in the Everglades feeds into the Biscayne Aquifer, the main water supply for Broward, Miami-Dade, Monroe and Palm Beach counties. Small-scale drought events have cropped up over the past two decades, leaving lasting impacts on the county’s water supply.

“Drought is a cancer. Its effects creep up little by little and you don’t notice them until it’s too late,” Abiy said. “You can’t predict when drought will happen. But, with the right information, you can design sound strategies to better store water in the Everglades, manage our water supply and take action immediately.”

March 27, 2018 (Source: FIU) - Seagrasses in Shark Bay, Australia released massive amounts of carbon dioxide after a devastating heat wave killed them, according to a new study.

March 27, 2018 (Source: FIU) - Seagrasses in Shark Bay, Australia released massive amounts of carbon dioxide after a devastating heat wave killed them, according to a new study.

More than 22 percent of Shark Bay’s seagrasses died when water temperatures warmed as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit above normal for more than two months in 2011. Up to 9 million metric tons of carbon dioxide were released — the equivalent of what is released annually by 800,000 homes or 1.6 million cars. Healthy seagrass meadows act as giant reservoirs that store carbon in their soils, leaves and other organic matter.

“As the Earth’s climate changes, we expect to see more and more intense heat waves,” said James Fourqurean, director of FIU’s Center for Coastal Oceans Research and co-author of the study. “This release of carbon to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide will only cause further heating of the atmosphere, heating of the oceans and climate change.”

March 22, 2018 (Source: UM CAS) - Conservationists and natural resource managers have lost ground over the past 20 years as more and more natural land—especially on the coast—has given way to homes and businesses, threatening the natural ecosystem.

March 22, 2018 (Source: UM CAS) - Conservationists and natural resource managers have lost ground over the past 20 years as more and more natural land—especially on the coast—has given way to homes and businesses, threatening the natural ecosystem.

University of Miami Associate Professor in Biology Kathleen Sullivan Sealey and her colleagues set out to find out why by investigating the ecology of finance and the financial innovations that have facilitated rapid housing development.

In a study published in the journal Anthropocene entitled, “Financial credit drives urban land-use change in the United States,” Sealey and her team borrowed concepts from ecology, finance, urban studies, and complex systems to develop a hypothesis about the fundamental shifts in the flow of money throughout the entire development and construction process.

The paper lays the foundation for a new area of research in the coupled human-natural systems linking modern finance to climate and ecological change.

“After three years of research that included a case study specific for South Florida, we found that the greatest attribute for the housing boom, from 1980 to 2008, was the key changes in banking regulations in the 1970s that allowed for increased availability of credit,” said Sealey. “The key component was the ability to transfer investment risks for developers and lending institutions.”

March 21, 2018 (Source: UF) - The face of American forests is changing, thanks to climate change-induced shifts in rainfall and temperature that are causing shifts in the abundance of numerous tree species, according to a new paper by University of Florida researchers.

March 21, 2018 (Source: UF) - The face of American forests is changing, thanks to climate change-induced shifts in rainfall and temperature that are causing shifts in the abundance of numerous tree species, according to a new paper by University of Florida researchers.

The result means some forests in the eastern U.S. are already starting to look different, but more important, it means the ability of those forests to soak up carbon is being altered as well, which could in turn bring about further climate change.

“Although climate change has been less dramatic in the eastern U.S. compared to some other regions, such as Alaska and the southwestern U.S., we were interested to see if there were signals in forest inventory data that might indicate climate-induced changes in eastern U.S. forests,” said Jeremy Lichstein, senior author and a UF assistant professor of biology. “The changes we documented are easily masked by other disturbances, which is probably why no one had previously documented them. Without a long-term dataset with millions of trees, we probably could not have detected these changes.”

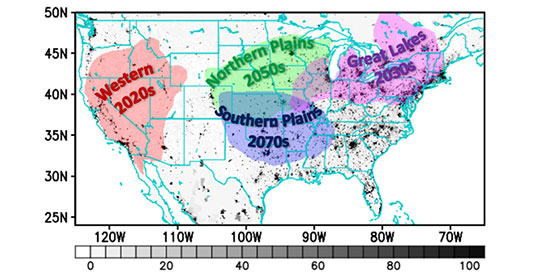

March 19, 2018 (Source: UM/RSMAS) Human-caused climate change will drive more extreme summer heat waves in the western U.S., including in California and the Southwest as early as 2020, new research shows. The new analysis of heat wave patterns across the U.S., led by scientists at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (UM) based Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Science (CIMAS) and colleagues, also found that man-made climate change will be a dominant driver for heat wave occurrences in the Great Lakes region by 2030, and in the Northern and Southern Plains by 2050 and 2070, respectively.

March 19, 2018 (Source: UM/RSMAS) Human-caused climate change will drive more extreme summer heat waves in the western U.S., including in California and the Southwest as early as 2020, new research shows. The new analysis of heat wave patterns across the U.S., led by scientists at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (UM) based Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Science (CIMAS) and colleagues, also found that man-made climate change will be a dominant driver for heat wave occurrences in the Great Lakes region by 2030, and in the Northern and Southern Plains by 2050 and 2070, respectively.

Man-made climate change is the result of increased carbon dioxide and other human-made emissions into the atmosphere.

“These are the years that the human contributions to climate change will become as important as natural variability in causing heat waves,” said lead author Hosmay Lopez, a CIMAS meteorologist based at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic Meteorological Laboratory. “Without human influence, half of the extreme heat waves projected to occur during this century wouldn’t happen.”

The study, published in the March 19, 2018 online issue of the journal Nature Climate Change, has important implications for the growing populations in these regions since heat waves, which are the number one cause of weather-related deaths in the United States, have already increased in number and severity in recent decades and are projected to rise well into the 21st century.

March 14, 2018 (Source: 100 Resilient Cities) - 100 Resilient Cities – Pioneered by The Rockefeller Foundation today released “Safer and Stronger Cities,” a series of policy recommendations for the federal government to help our nation’s urban centers become more resilient in the face of 21st-century challenges. The report, which comes after cities faced an unprecedented series of short-term and long-term challenges in 2017, focuses its recommendations on infrastructure, housing, flood insurance, economic development, and public safety.

March 14, 2018 (Source: 100 Resilient Cities) - 100 Resilient Cities – Pioneered by The Rockefeller Foundation today released “Safer and Stronger Cities,” a series of policy recommendations for the federal government to help our nation’s urban centers become more resilient in the face of 21st-century challenges. The report, which comes after cities faced an unprecedented series of short-term and long-term challenges in 2017, focuses its recommendations on infrastructure, housing, flood insurance, economic development, and public safety.

Access the full report here: www.100resilientcities.org/safer-and-stronger

February 21, 2018 (Source: American Institute of Biological Sciences via ScienceDaily) - The linkages between environmental health and human well-being are complex and dynamic, and researchers have developed numerous models and theories for describing them. They include attempts to bridge traditional academic boundaries, uniting fields of study under rubrics such as social-ecological frameworks, coupled human and natural systems, ecosystem services, and resilience theory. However, these efforts have been constrained by varying practices and a failure among practitioners to agree on consistent practices.

Writing in BioScience , Jiangxiao Qiu of the University of Florida and his colleagues describe this state of affairs and propose an alternative and practical approach to understanding the interplay of social and ecological spheres: causal chains. The authors describe these chains as an "approach to identifying logical and ordered sequences of effects on how a system responds to interventions, actions, or perturbations." And although causal chains are well established in many fields, the authors highlight that "there is no normative consensus about the principles and guidelines necessary to create causal chains relevant for dealing with human-nature challenges."

By refining and standardizing the causal chain methodology, the authors hope that the drivers of human behavior, and inherently linked social and ecological outcomes can be better understood -- and then acted on. For instance, the authors cite an example of a biophysical system in Kenya in which forests are converted to farmland without the supply of additional nutrients. Without intervention, the consequent soil degradation then results in "food insecurity and reduced household income, while further accelerating the degradation of the remaining forests."

By viewing this cycle through the lens of causal chains, managers might be better able to see ways to break it. Qiu and his colleagues describe a three-phase system for identifying and working with causal chains, designed to permit the assessment of current systems and their responses to management actions. Possible targets for study include food production and pollution interactions, land-use change and its effects on local populations, and the responses of natural and social communities to climate-change-induced severe weather events.

February 8, 2018 (Source: FAU) - Who’s your daddy? No, it’s not a TV clip from “The Jerry Springer Show” to identify who the “real” father is. Rather, it is a groundbreaking study of sea turtle nests and hatchlings using paternity tests to uncover “who are your daddies?”

February 8, 2018 (Source: FAU) - Who’s your daddy? No, it’s not a TV clip from “The Jerry Springer Show” to identify who the “real” father is. Rather, it is a groundbreaking study of sea turtle nests and hatchlings using paternity tests to uncover “who are your daddies?”

The study conducted by researchers at Florida Atlantic University and published in PLOS One , is the first to document multiple paternity in loggerhead sea turtle nests in southwest Florida. What started out as a study on female sea turtle promiscuity – females can have multiple partners and can store sperm for more than three months after mating events – is proving to be very good news for this female-biased species facing rising risks of extinction due to climate change.

Due to their accessibility, nesting female sea turtles, nest success, and hatchlings are frequently examined and used for demographic studies and population models (key areas for the management of imperiled species). Yet, there is very limited understanding of the proportion of adult males and males approaching sexual maturity in any sea turtle population. Consequently, male sea turtles’ reproductive behavior is poorly understood and adult sex ratio cannot be estimated directly.

“Studying sex ratios of adult sea turtles in the ocean is logistically difficult because they are widely distributed and males are especially difficult to access because they rarely come to land,” said Jacob Lasala, corresponding author of the study and a Ph.D. student working with Jeanette Wyneken, Ph.D., co-author and a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at FAU’s Charles E. Schmidt College of Science. “We decided to use a different approach and measure ‘breeding sex ratios’ using genotyping to examine the number of male sea turtles that contribute to nests.”

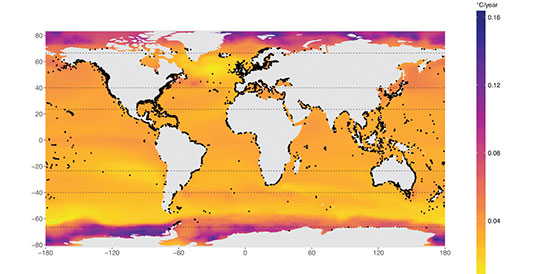

February 12, 2018 (Source: USF) - Twenty-five years of satellite data prove climate models are correct in predicting that sea levels will rise at an increasing rate. In a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers found that since 1993, ocean waters have moved up the shore by almost 1 millimeter per decade. That’s on top of the 3 millimeter steady annual increase. This acceleration means we’ll gain an additional millimeter per year for each of the coming decades, potentially doubling what would happen to the sea level by 2100 if the rate of increase was constant.

February 12, 2018 (Source: USF) - Twenty-five years of satellite data prove climate models are correct in predicting that sea levels will rise at an increasing rate. In a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers found that since 1993, ocean waters have moved up the shore by almost 1 millimeter per decade. That’s on top of the 3 millimeter steady annual increase. This acceleration means we’ll gain an additional millimeter per year for each of the coming decades, potentially doubling what would happen to the sea level by 2100 if the rate of increase was constant.

“The acceleration predicted by the models has now been detected directly from the observations. I think this is a game-changer as far as the climate change discussion goes,” said co-author Gary Mitchum, PhD, associate dean and professor at the University of South Florida College of Marine Science. “For example, the Tampa Bay area has been identified as one of 10 most vulnerable areas in the world to sea level rise and the increasing rate of rise is of great concern.”

February 5, 2018 (Source: USF) - Researchers at the University of South Florida have offered a deeper understanding of climate change effects on animal phenology in their study, "A global synthesis of animal phenological responses to climate change", published this week in Nature Climate Change.

February 5, 2018 (Source: USF) - Researchers at the University of South Florida have offered a deeper understanding of climate change effects on animal phenology in their study, "A global synthesis of animal phenological responses to climate change", published this week in Nature Climate Change.

By examining more than a thousand records of these phenological shifts dating back to the 1950s, the study revealed that various taxa, like insects, birds, amphibians and mammals, are shifting their seasonal activities at different rates in response to a changing climate.

“We found that cold-blooded species and those with small body sizes are shifting their phenological activities faster, or track changing climates more effectively, than warm-blooded or large-bodied species,” said the study’s lead author Jeremy Cohen, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the USF Department of Integrative Biology. “These differences could potentially cause mismatches between interacting species, such as migrating birds and their prey.”

The study also provides the first evidence that different locations have different drivers of climate change-induced phenological shifts. For example, at temperate latitudes, multidecadal trends in temperature were associated with phenological shifts, whereas at tropical latitudes, it was trends in precipitation. Jason Rohr, PhD, a USF professor and co-author of the study, explained that these patterns are sensible because seasonality is generally driven by temperature in temperate regions and rainfall in tropical regions.